On January 6, 1978, Judge Neil McKinnon presided over the trial of John Kingsley Read, the former chairman of the National Front and the founder of a new far-right organisation, the National Party. Read stood accused of inciting racial hatred for a speech in which he used several unambiguously racist terms, including the n-word, and said of the recent murder of an Asian man, Gurdip Singh Chaggar, “one down, a million to go”.

McKinnon advised the jury to acquit Read, saying that the racial slurs were not in themselves unlawful. He argued that their impact depended on their “circumstances and their intent”, adducing their use in nursery rhymes as evidence that they were not necessarily malicious.

He described Read as “obviously a man who has had the guts to come forward in the past and stand up in public for the things that he believes in”. After the jury had acquitted Read, McKinnon told him, “I wish you well.”

The judge’s words provoked national fury. More than 100 MPs called for his resignation. To Sibghatullah Kadri, the founder of Britain’s first multiracial chambers at 11 King’s Bench Walk, in central London, McKinnon’s well-wishing of Read was an outrage but not a surprise.

Kadri had founded his chambers in 1973 after years of unsuccessful struggle to attain tenancy elsewhere. At the time there were, by his count, no more than ten ethnic-minority barristers practising in Britain, and no Queen’s Counsels. Many solicitors refused to brief ethnic-minority barristers, on the basis that clients, judges and juries preferred white British ones. So to Kadri, McKinnon’s words merely added to the superfluity of evidence that the legal system was institutionally racist.

Though racism in his profession seemed pervasive, that did not sap his energy to fight it. Kadri was well known to the Bar as a troublemaker, having organised, while a student, the first sit-in at the Inns of Court School of Law.

The sit-in, which was part of a campaign for students to be allowed to unionise, as well as to highlight that British students received more tuition than Commonwealth ones, made the front page of The Times. Kadri was also the co-founder of the Society of Afro-Asian and Caribbean Lawyers, renamed in 1981 the Society of Black Lawyers.

In response to McKinnon’s comments, Kadri told journalists that he and 20 other barristers from an ethnic minority would boycott his courtroom. The Bar Council then invited him in for a discussion. “But it turned out that it wasn’t actually concerned with McKinnon’s behaviour,” he recalled. “It was our behaviour that was unacceptable. We refused to back down, and though there was no formal censure of the judge at all, the lord chancellor eventually let it be known that McKinnon would ‘prefer’ not to hear ‘comparable’ cases again.”

In the early 1980s, Kadri defended people accused of taking part in the Bristol and Brixton riots, as well as the Bradford Twelve, a group of anti-fascists charged with manufacturing explosives for what they claimed was “defensive use”.

Before defending a group alleged to have taken part in the Bristol riots, he and his team requested that the composition of the jury be changed to better reflect the ethnic diversity of the population. This use of “peremptory challenge” had centuries of precedent, but that did not deter the criticism of Lord Denning, the Master of the Rolls.

In his 1982 book What Next in the Law, Denning accused Kadri and his team of “packing” the jury with “coloured” jurors, many of whom — he alleged — came from countries “where bribery and graft are accepted as integral parts of life”. Denning argued that juries should no longer be selected at random because “the English are no longer a homogenous race. They are white and black, coloured and brown. They no longer share the same standards of conduct.”

Kadri, in his capacity as chairman of the Society of Black Lawyers, called for Denning’s resignation, saying that his remarks were “virulent enough to destroy any remaining credibility he may have as an unbiased and impartial interpreter of the law”.

The demand was met. The book was withdrawn from sale. Denning retired, and later apologised for writing what he had — a sign that Kadri, while an object of suspicion to conservatives in the Inns of Court, was not a pariah. He earned his views a hearing through sheer force of argument, obliging his white colleagues to notice the ways in which the supposedly impartial legal system systematically mistreated ethnic minorities.

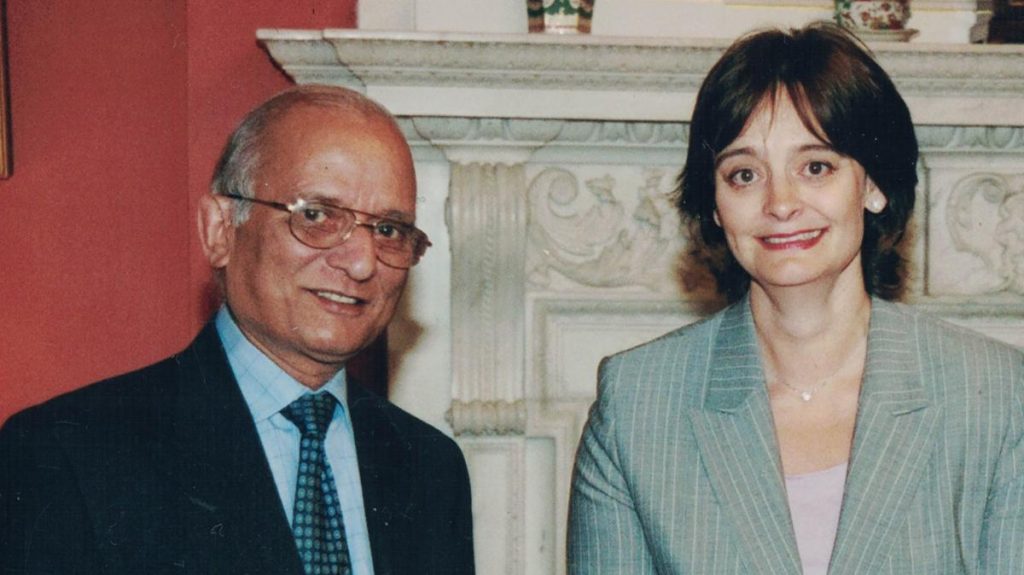

That the Bar listened to his message is reflected in the fact that, in 1989, Kadri became Britain’s first Muslim Queen’s Counsel, and eight years later was appointed a bencher of the Inner Temple.

Sibghatullah Kadri was born in Budaun, a city in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, in 1937. The family, middle class and devoutly Islamic, moved to Pakistan in 1949, two years after partition. Kadri later said that, in moving, he was “losing my childhood as I had to leave my close friends behind”. The Kadris expected a comfortable life in Pakistan. Instead, in Karachi, Sibghat, his parents and his seven siblings shared a single room.

In 1956 he enrolled at Karachi University to read chemistry and mathematics, and became active in student politics. Elected the head of the students’ union, he spoke out against the martial law of President Ayub Khan. He was initially a diffident speaker, but soon found that he could quell his nerves by marshalling facts. In 1958 he was jailed for seven months for his opposition to Khan. He drafted his own writ of habeas corpus, submitted it to the Pakistani high court, and secured his release, but was barred from completing the final year of his studies. In 1960 his sister, already in England, was seriously injured in a fire. The entire Kadri family came to visit her in hospital. Although she died two weeks later, they remained.

In 1961 he was admitted to the Inner Temple even though he did not have an entrance qualification, on the basis that he should not be punished twice for his activism. He later recalled that this initial view of the legal profession was “starry-eyed”. He felt privileged to be training in the same rooms as Gandhi, Nehru and Jinnah, the architects of Indian independence.

While studying for his Bar exams he worked as a postman, a clerk and a waiter in an Indian restaurant in Kilburn where, one evening in 1963, a white customer slashed his face with a knife after refusing to pay his bill.

That year he married Carita Idman, a Finnish au pair. They had two children, Sadakat, who became a barrister and writer, and Maria, who went on to work in local government and as a teacher. All survive him.

In 1964 he took a job as a newsreader for the BBC Urdu service. Embarking on his Bar finals course in 1968, he helped set up the Bar Reform Committee. Having won the right to unionise, he defeated John Laws, the lord justice of appeal to be, to become the president of the Inner Temple Students’ Association. When he next went into the BBC offices he was told he would no longer be reading the news because “you are the news”.

His next appearance in the headlines was in 1970 when, at a rally to protest against the murder of a Bengali immigrant in London’s East End, he reminded the crowd that the law allowed them to defend themselves. He told a Daily Telegraph reporter that while the Asian community was not looking for trouble, “they will be ready to deal with it”. For this he was sacked from his second job at the Urdu service, where he had been presenting a magazine show.

In 1971 he was offered pupillage by Lord Anthony Gifford. Despite this break, he struggled to get tenancy, so in 1973 founded his own chambers.

Not once in his career did he prosecute because, he said, he wanted to direct his efforts to defending those he felt the legal system did not allow a fair hearing. “It is wrong to say that a lawyer is just a cog in a machine,” he said. “The question is which part of the machine do you want to assist?”

In court, Kadri was a fierce and deep-voiced rhetorician. He once brought a jury to tears by comparing a group of Kosovans, who had used fake Italian identity cards to escape their country’s conflict, to Jews fleeing the Holocaust. “He was a tiger,” said his friend the barrister Arthur Blake, “but he had a soft underbelly.”

After receiving news of his death, the Inner Temple flew its flag at half-mast. When an extension to its treasury building is finished next year, a photograph of Kadri will hang there, commemorating him as Britain’s first Muslim QC.

Last year, reflecting on how attitudes to race in the legal profession had changed across his career, Kadri said: “The situation is vastly improved. A generation of lawyers has grown to maturity knowing racism to be wrong. There’s still plenty to be done — only recently, it was in the news that a black barrister was mistaken for a defendant, after all — but it’s impossible to believe that things will ever be as bad again.”

Sibghatullah Kadri, Queen’s Counsel, was born on April 23, 1937. He died of cancer on November 2, 2021, aged 84