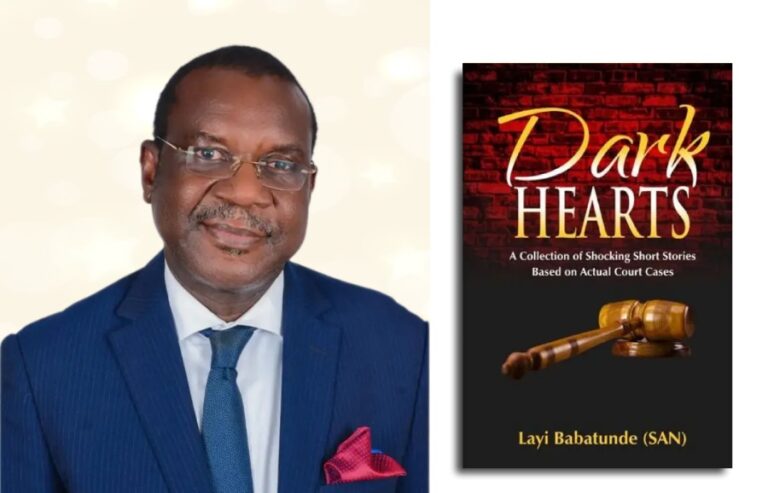

In Dark Hearts, Layi Babatunde, a Senior Advocate of Nigeria, who has been in legal practice for close to four decades, brings into the open, in simple prose, what would otherwise have been buried in Law Reports and other legal literature. He delivers a chilling account, which would make you ponder, on the increasing loss of humanity amongst humans using a collection of short stories.

Evidently aided by the legal luminary’s well-known interest in scholarship and incursion into law reporting through the Supreme Court Reports (S.C Reports) which he has edited and published for decades, Dark Hearts is a collection of 12 short stories based on actual life occurrences, leading to prosecution under the Laws of Nigeria and decisions rendered up to the Apex Court. The case references or citation are in the End Note.

And as the author says in his introduction, some of the revelations in the collection would make the average person shudder at man’s limitless capacity for evil. The stories distilled from cases decided by the Supreme Court at diverse times, also amply tells that the pervasive cold-heartedness and lack of fellow feeling with which Nigeria currently grapples may in fact be as old as humanity itself, Indeed Nothing is truly new!

From murder to armed robbery to kidnapping, ritual killings and even the desecration of worship places in the perpetration of evil for selfish gains, Nigeria is only currently seeing an escalation rather than a novelty.

One would imagine that this is one of the concrete benefits that this timely book has for its readers. By rousing their consciousness, the book reminds them that they have always had the tendency to jettison blood ties and affinities and sacrifice a brother and sister for the sake of becoming rich.

Thus, Dark Hearts compels sociologists and psychologists in Nigeria to probe beyond the general assumption that the current economic downturn and government’s inability to actualise shared prosperity amongst its 200 million citizens is what is turning Nigerians into money-mongering savages. This is one of the myths that Babatunde busts in his collection of stories. In one of the stories, “Brother Kills Brother”, a man leaves Kano, in the north-west of Nigeria all the way to Iwo, in the south-west to source for a hunchback required for a money ritual for some men who were desperate to be rich. And you wonder at the depth of darkness of this man’s heart when you realise that he merely facilitates evil for people other than for himself and that the hunchbacked man he was ready to sacrifice turns out to be his own younger brother!

The reader is also confronted with issue of unsafe school environment, the kidnapping of children either for ransom or ritual purposes. In “Ex-employee from Hell”, a former domestic worker kidnaps the son of his old employer from school for a ransom. But the story does not end well. The story in “Gruesome Murder of a Child” is similar expect that this time around, the crime is masterminded by an uncle, who knew the itinerary of the abducted child’s parents. Again, the motive is money ritual.

And then there are a variety of stories dwelling on armed robberies, murders, and kidnapping (including that of a magistrate) and betrayal. A memorable one is the story entitled “Band Manager Kills Band Leader”, which would resonate with people conversant with the story of a popular musical artist who was murdered in south-west Nigeria about four decades back. And for this artiste, it seems 2020/2021 is unwittingly commemorative given the fact that production work has just been completed on feature film by the legendary filmmaker Tunde Kelani.

Given his pedigree with the Supreme Court Reports, questions could be raised as to whether Dark Hearts is an extension of Babatunde’s contribution to the documentation of case law in Nigeria. This is more so because many of the stories in the collections went as far at the Supreme Court for final determination.

This question would not be far-fetched because in a sense; this book, in spite of the attempt to introduce elements of fiction into it, tells of the tenacity and consistency of the legal system in Nigeria. From the trial court through to the supreme court, the flavour of judgement is largely consistent, something which lends credence to the competence of Nigerian judges in spite of increasing public disaffection.

It is clear though that the author did not set out to do a work of fiction à la John Grisham novel. A ready evidence of this is in the fact that the title of some of the stories, leave little or nothing for imagination as one would expect in fiction. For example: does “Gruesome Child Murder” and “Murder in Church” not already tell the reader most if not all of the story?

The good thing however, is that the writer does not pretend to be giving Nigeria a work of fiction. The registers, style, mood, and pace employed in all these stories are largely reportorial and serve the purpose of reminding Nigerians, that the heart of man has always been “desperately wicked.” Lessons obviously can be learnt, from the stories and their outcome that evil does not pay! In addition to that, Babatunde does one more thing for Nigeria: bringing legal stories into print in the mode of true stories that flirt with fiction.